A Tale of 2 Bike Rides

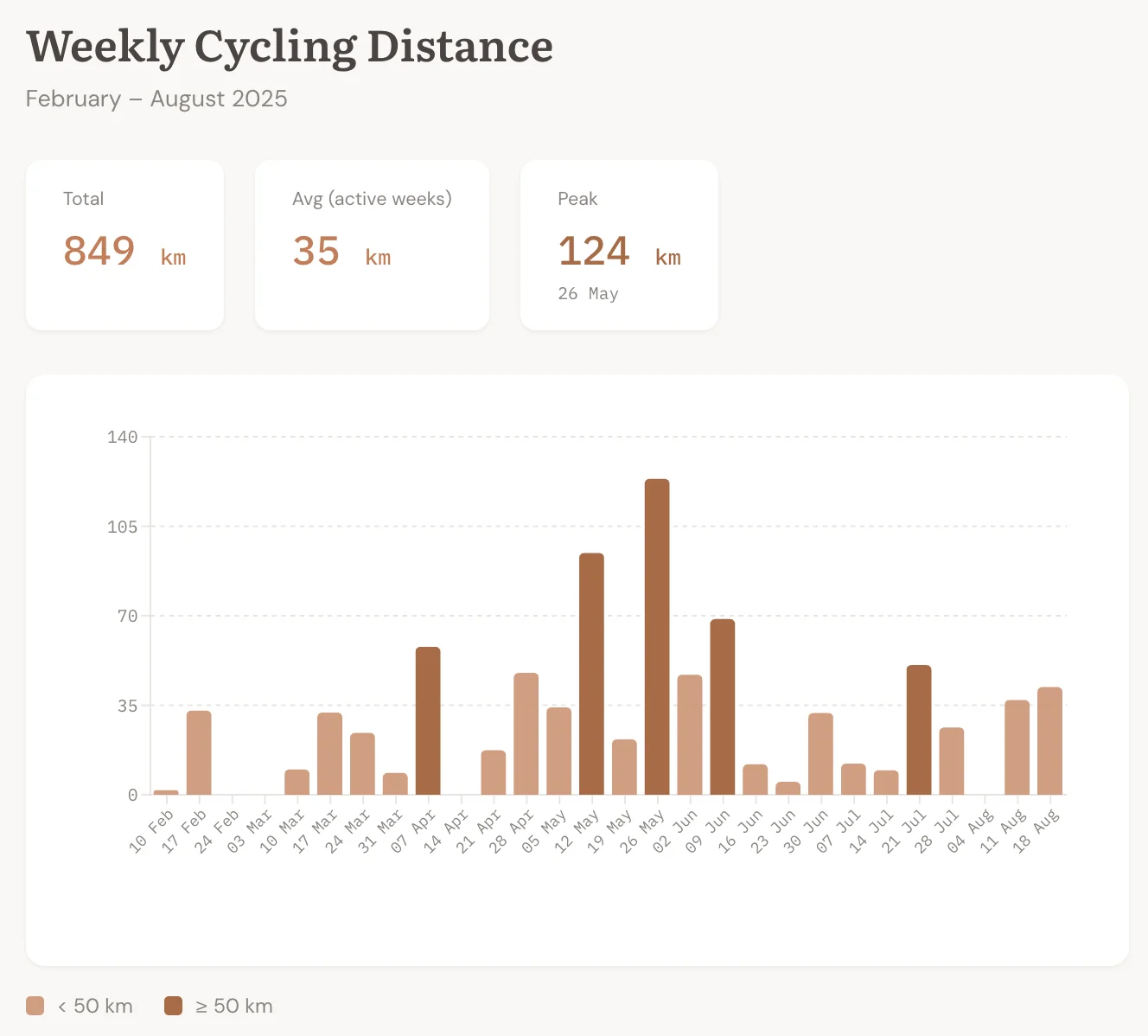

This started when I registered for the London to Brighton charity bike ride. 90 kilometres, scheduled for June 15th. I trained through spring, building up my mileage from April onwards.

A month before the event, I had a 67 km ride that made me feel like a star. I felt like I could stretch to 100km easily.

Two weeks later, I took a course of antibiotics for an unrelated issue. My next long ride? I bonked at 43km with a splitting headache. My brain wanted to shut down. I limped home defeated.

Same body. Same training. What changed?

To answer that, I had to understand what was actually happening inside my cells during those rides. And what I found was fascinating: the first ride taught me how the system works when it works. The second taught me how easily it breaks when gut bacteria suffer from a mass murder at the hands of antibiotics.

Source: My annoying Garmin

Source: My annoying Garmin

Richmond Park, Sep 2024 - from my longest ride ever (100km)

Richmond Park, Sep 2024 - from my longest ride ever (100km)

The ride where I was flying

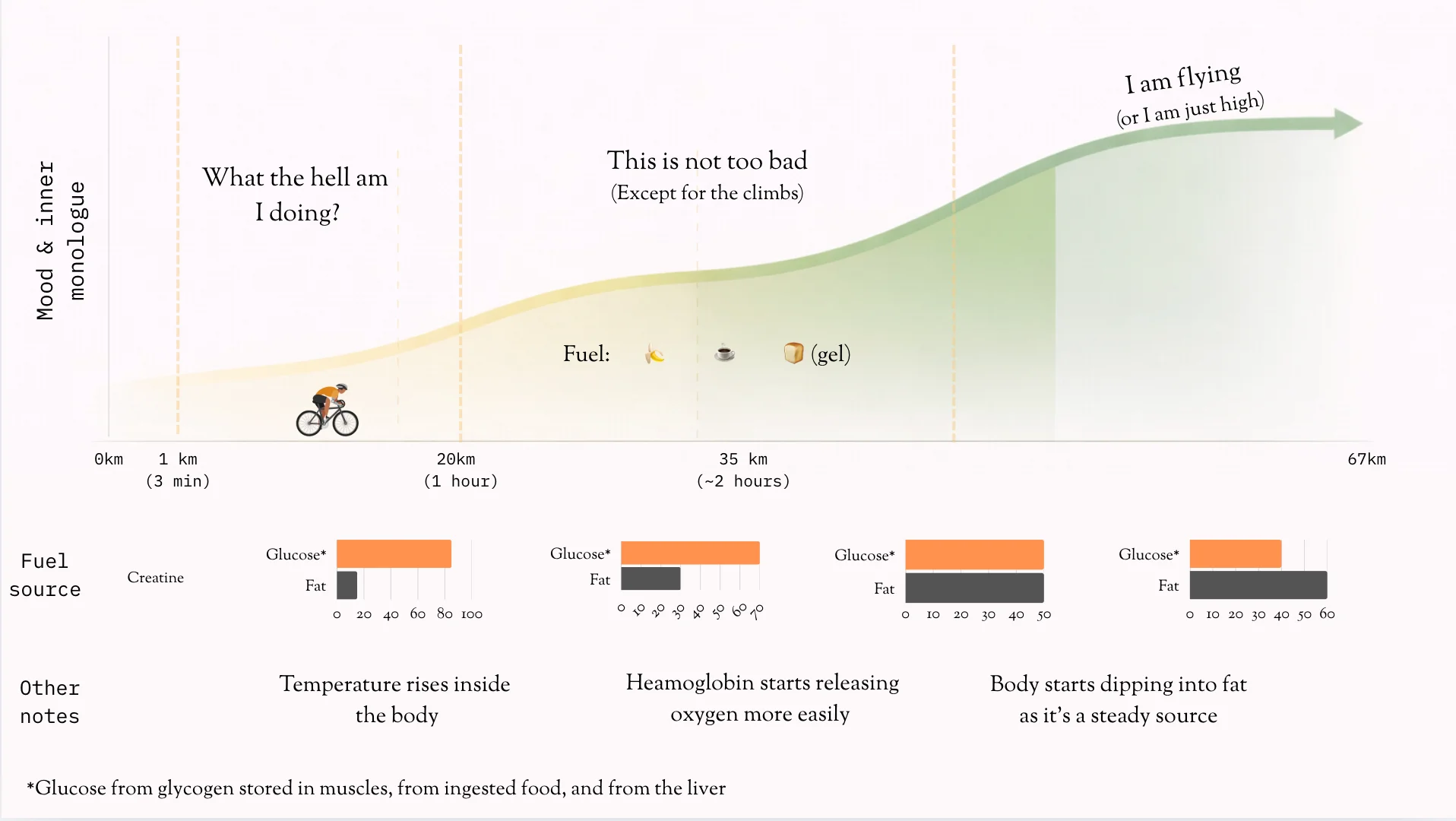

One of the bike rides had me feeling like a star. It was a solid 67 km (It’s the new 69 after all). Though initially, it was a bit of a drag, and I was wondering why did I even step out that day. But than after 20km into the ride, with proper fuelling, things clicked despite the multiple inclines. In fact, I was deliberately training through a lot of ascents because London Brighton route is not a flat one - it has a killer ascent right at the end. I felt strong coming back and overtook several Lime bikes around Hyde Park while silently judging them. But what struck me was how the hell did I go from “Why did I even step out today” to “I’ve got this, and can stretch till 100km easily”. I was buzzing with questions. One main question was “How exactly does this all of this work?”.

While I had an idea of energy systems from the podcasts I usually listen to, I wanted to dig deeper. I used the notes I took after the workout and discussed those extensively with my best friends - Claude, ChatGPT and Gemini to understand this better.

Some spoilers in this infographic here and please note that these are representative numbers

Some spoilers in this infographic here and please note that these are representative numbers

How do the energy systems in the body work?

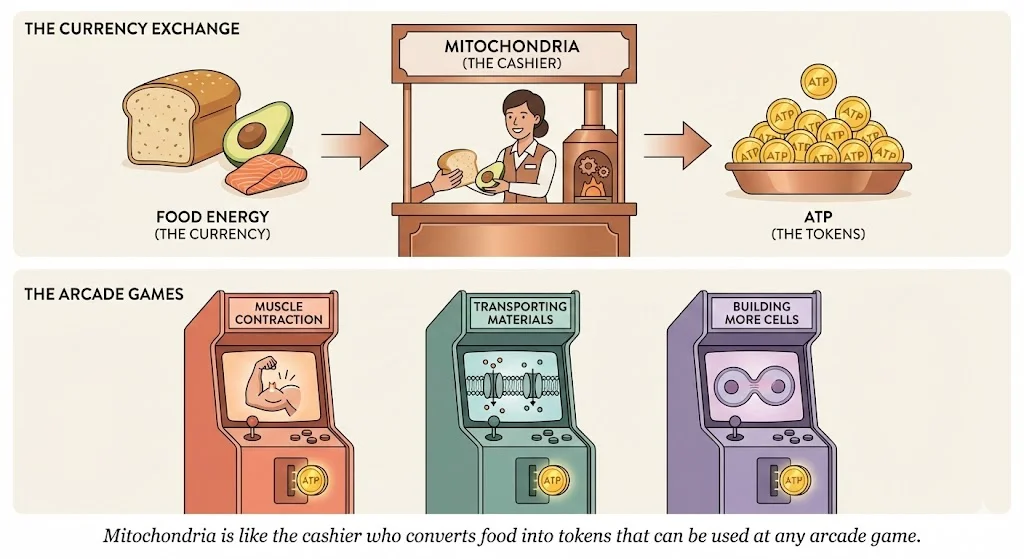

What you need to understand here is that mitochondria, often called the powerhouse of the cell, is actually like a cashier in an arcade. Your cell can use any currency it has (fat or carbs) and trade it for tokens (molecules called ATP) that can be used to play any game in the arcade. Simply put, ATP is the token your cell uses to contract muscles, transport materials, or make proteins.

Going forward, remember that we can use this analogy almost anywhere.

Now when you start any activity, like my bike ride, a sequence of fascinating mechanisms kick into gear. The initial steps are always anaerobic. The anaerobic steps always take place outside the mitochondria, and as the name suggests, in the absence of oxygen.

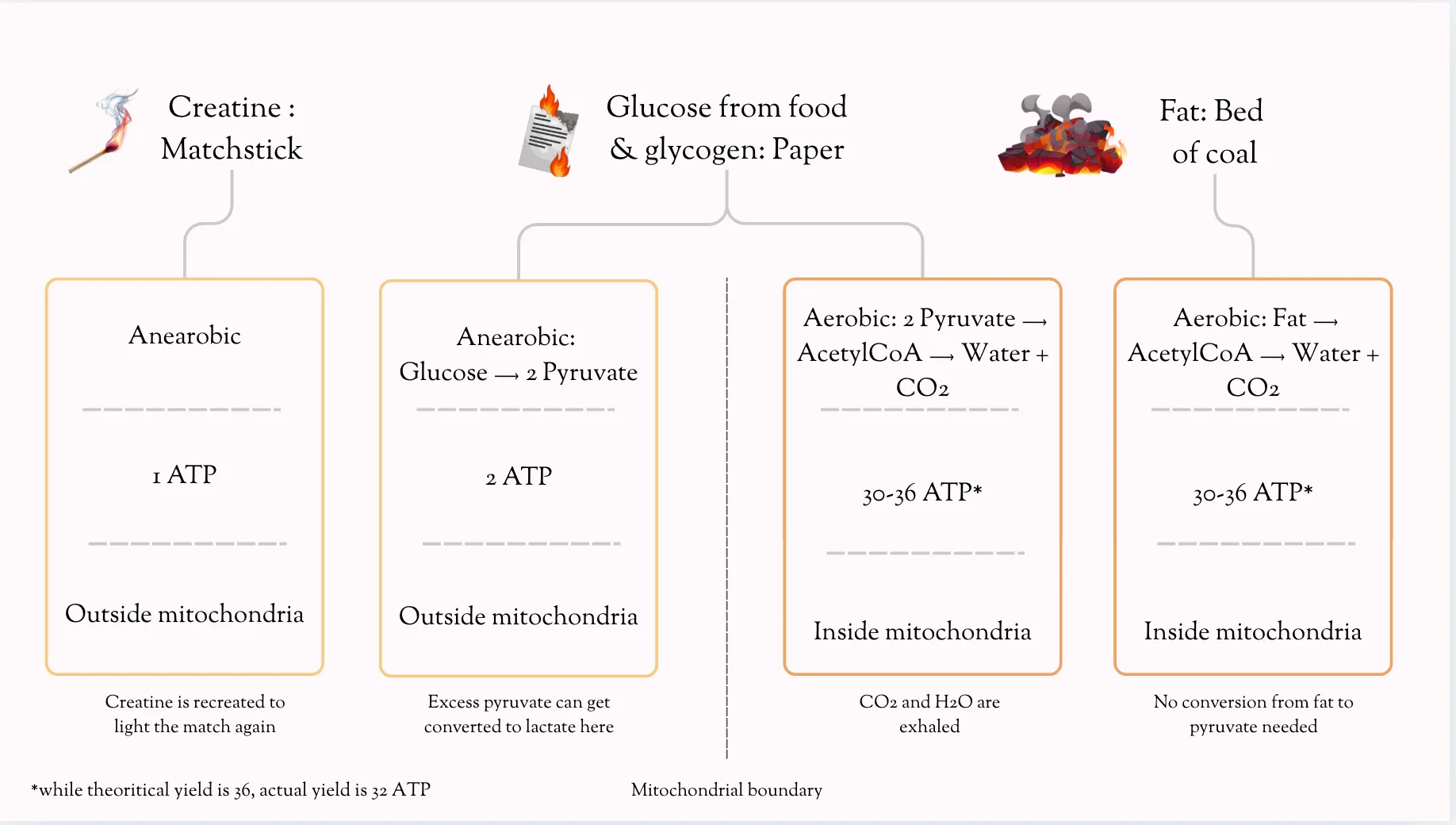

Step 1: Phosphocreatine

The first step is the utilisation of phosphocreatine. This is the same substance that powerlifters take to enhance their performance in the gym. Because phosphocreatine is first in line to meet any extra energy demand, you can see why it all makes sense.

Keep in mind that 1 phosphocreatine molecule yields 1 ATP in the process. The yield of this reaction is 1 token of energy that the cell can use to send contraction signals down the muscle.

Step 2: Anaerobic breakdown of glucose

The second step in the process is the anaerobic breakdown of glucose. This glucose can come from two sources: the glycogen stored in your muscle, or the glucose circulating in your blood. Muscles love to first dip into their own glycogen reserves as glycogen is just glucose and water. Also, muscles are picky about glycogen use. While they love to dip into their reserves, they are stingy about releasing it back into the bloodstream. That’s what makes them a great place to store excess sugar.

Glucose (which has 6 carbon atoms) breaks down into two molecules of something called pyruvate (which has 3 carbon atoms). This process releases 2 molecules of ATP.

Step 3: Aerobic glycolysis

Now pyruvate is ready to enter the mitochondria for aerobic glycolysis, which is a fancy way of saying that it is ready to get “burnt” inside the marvellous mitochondria in the presence of oxygen, which you have been breathing. Mitochondria burns off the pyruvate and yields water, carbon dioxide and 30-36 molecules of ATP.

Take a breath there. This is 30 times the phosphocreatine yield and 15 times the yield of the previous step. Your cell now has plenty of tokens to play the arcade games it wants.

But what about fat?

Matches, paper and coal

We have discussed how glucose undergoes aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis. But what about fat, and what about protein?

Well, to borrow an analogy from Dr. Andy Galpin: phosphocreatine is like a match, glucose is like paper, fat is a bed of coals, and protein is like a piece of metal. The match starts the fire and burns itself very quickly. The paper burns quickly too, but as long as there is enough paper, you can keep burning it. The bed of coals takes a while to get started but gives you steady and consistent output. The metal hardly burns at all, and thus protein is not a good fuel source to make ATP. But if the body wants, it can bloody well use protein as a source. Anyway, let’s take a look at how your cells use fat as a fuel. Spoiler alert - it need not get converted to pyruvate to be used.

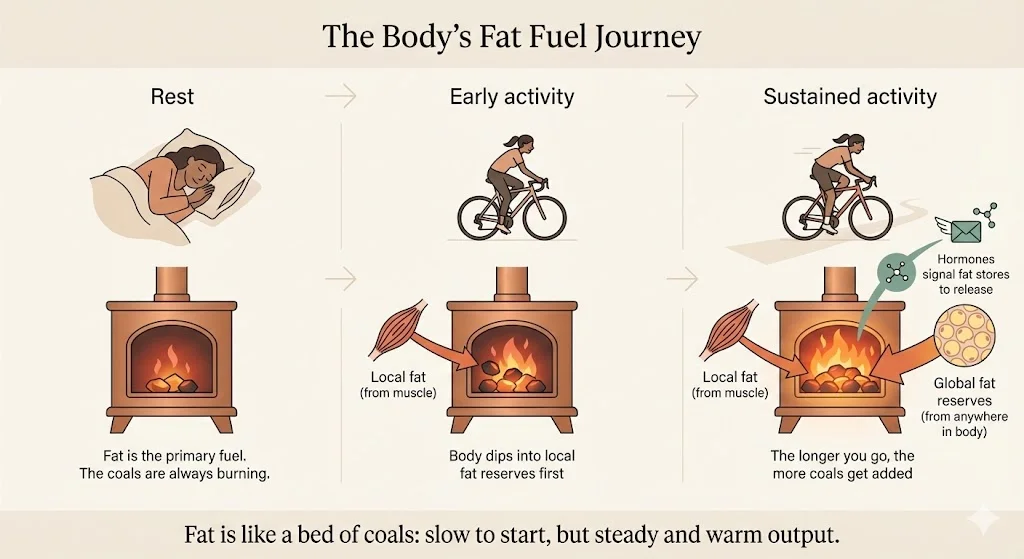

The fat burning cascade

First off, your body is almost always burning fat. The coals are always burning. Your body relies on fat for low intensity stuff - like sleeping or slow walking. When you sleep, your body loves to use fat as a fuel source (And no, I am not implying that you can just sleep your fat off forever). Once demand increases, as we have seen, it first uses creatine, and then glucose (from glycogen and food). And then it adds a few more “coals” to the furnace. First it sources the coals locally (from your muscle) and then it starts dipping into your global fat reserves - which can be anywhere in the body. Your Hormones (e.g. Adrenaline) are the master coordinators in this process. They signal the fat stores to release their cargo into the blood.

Fat oxidation is aerobic

Your mitochondria is pretty adept at burning fat, and it’s the only place where fat oxidation can actually take place. When you are long into a ride or a hike or any physical activity, your muscles start dipping into local and global fat reserves and transporting them to mitochondria, which dutifully burns them off.

The magical bit about this: fat burning is aerobic and usually doesn’t involve any anaerobic steps. Your mitochondria cleave off the fat molecules, convert them into acetyl-CoA, and then burn it off just like the byproduct of glucose. And if you continue to do steady state work for longer, your body starts increasing the share of fat as a fuel source. Because it’s like a bed of coals: slow, steady, and warm output.

What happens when you increase the workload?

It is important to keep in mind that this whole thing is a system in constant flux. It helps to think in terms of supply and demand. Think of the mitochondria as the “supply” for ATP (the tokens) to the cell as it “demands” ATP to send contraction and expansion signals for the muscle to do the work.

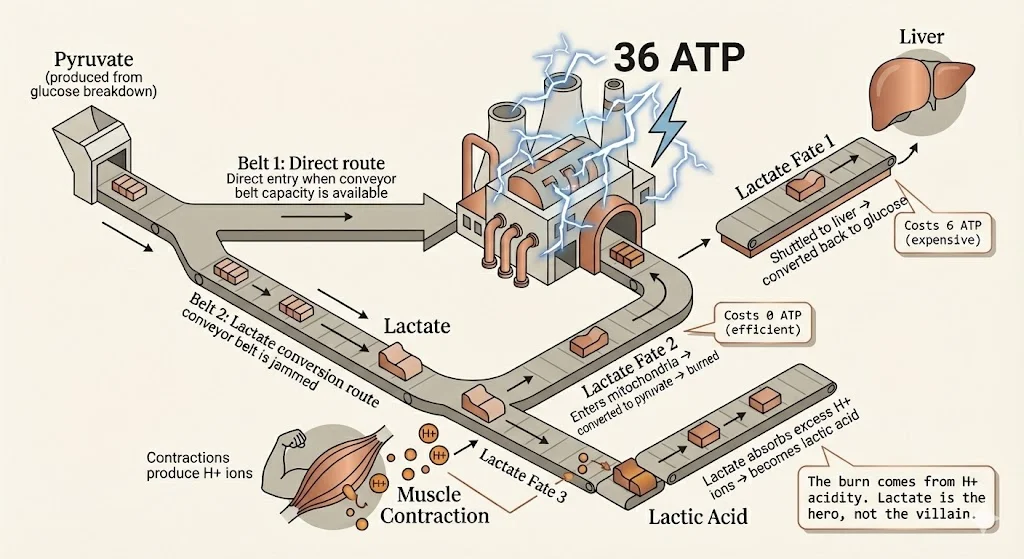

A couple of things can happen when you increase the workload. Think of the cell as a factory that needs conveyor belts to transport materials to and from it. So when workload increases, the cell’s ability to handle it boils down to the number of conveyor belts (how many?) and the capacity of these conveyor belts (how fast, and how much?).

Say the demand increases suddenly. You have to climb a hill or overtake someone on the bike. The phosphocreatine lights up again, followed by anaerobic breakdown of glucose which leads to the production of pyruvate. Now, your mitochondria would love to suck in the pyruvate as fast as possible. But if the conveyor belt system is slow or jammed, then the pyruvate sits around outside the mitochondria and gets converted to lactate very easily. So what does the lactate do now?

The 3 fates of lactate, and why burn isn’t lactic acid

Now here’s something you need to know about lactate: it is a great fuel. Pretty much any muscle in the body can use it. All the muscle needs to do is convert the lactate back to pyruvate (check fate 2 below), which requires some energy input but not a lot.

Depending on how well trained you are and your body’s preference in that moment, lactate can meet any of the following fates:

Fate 1: Lactate is shuttled back to the liver by the blood, where the liver converts it into glucose. This is metabolically expensive and costs 6 ATP to produce 1 glucose molecule from 2 lactate.

Fate 2: Lactate is shuttled directly to the mitochondria, where the mitochondria converts it back to pyruvate and burns it in the presence of oxygen. This costs 0 ATP to do and is energy efficient.

Fate 3: For the third fate, let’s take a step back. Remember that there is also a demand side in the cell. ATP is being consumed to cause contractions in the cell. If too many of these contractions happen, it creates an excess of hydrogen ions (H+), which causes acidity. This acidity is what gives you “the burn” in your muscles. Now if lactate is present in the cell and is sitting around, it dutifully absorbs these hydrogen ions and becomes lactic acid. In summary: lactic acid is because of poor lactate’s sacrifice and not the cause of the burn. The cause of the burn is acidity from muscle contractions.

What happens when you train more often in Zone 2?

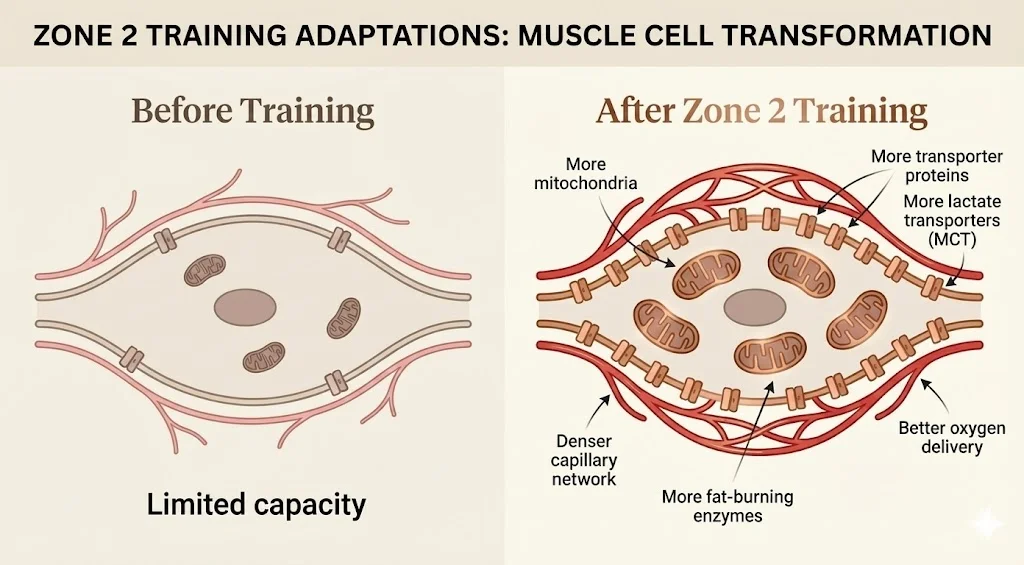

When you train consistently at a steady aerobic pace, your body adapts in remarkable ways.

It gets better at burning fat. Zone 2 training increases the number of blood capillaries that bring more oxygen, fat, and nutrients to your muscles. It also increases the number of transporters that act like doormen, shuttling fat into the mitochondria. And the mitochondria ramps up production of enzymes that chop up fat, making it easier to burn.

It builds better conveyor belts. Training increases the transporters that shuttle pyruvate and lactate directly into the mitochondria. This is hugely efficient because the lactate doesn’t have to travel all the way to the liver to be converted back to glucose.

It creates more powerhouses. Provided you eat well, your body creates more mitochondria. More factories means more ATP production capacity.

It handles lactate better. Your body builds more MCT transporters (monocarboxylate transporters) that shuttle lactate where it needs to go. Lactate becomes fuel instead of waste and suffers fate 2 instead of fate 1, helping conserving energy.

This is what I had built up over months of training. This is why I felt like a star on that 67km ride. Little did I know that I was going to have my ego checked intensely.

The ride where everything broke

About 10 days before the London to Brighton, I took a course of antibiotics for a dental infection. I didn’t think much of it. I set out on a training ride two days after finishing the course.

The first 20km were fine. The stretch from Lambeth to Richmond via Chelsea is lovely. Parts of it run along the river, and on the busier stretches around Putney and Chelsea, I got to overtake Ferraris stuck in traffic. But as I reached Richmond Park on that grey day, I noticed it was unusually quiet. Not the usual hustle of a Saturday. Things didn’t seem as bright and sunny.

At 30km, my thinking started to get fuzzy. My eyes were shutting down but my legs kept moving. I was struggling to keep my attention on the road. I thought it must be temporary so I stopped for food and felt better. But 5km later I was deteriorating again despite having just eaten. By 43km, I was having a splitting headache, my eyes wanted to shut down, and I could not easily maintain my focus on the road. I popped two panadols and decided to take the train back home after resting for a bit.

What went wrong

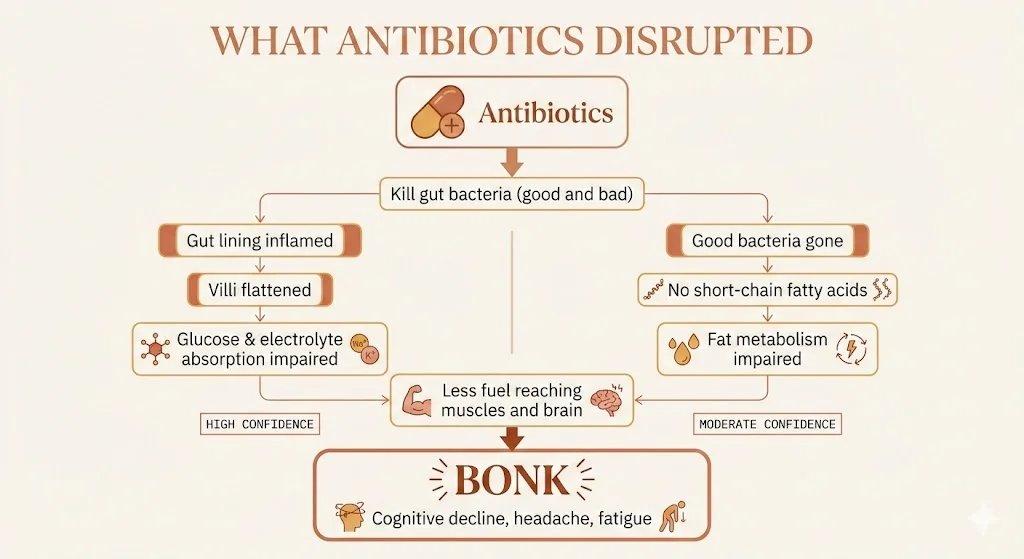

Antibiotics are indiscriminate killers - they are mass murderers. They wipe out the good gut bacteria along with the bad, and mind you there are as many bacteria in the human body as there are human cells. And those good bacteria aren’t just passengers - they help you digest food, absorb nutrients, and produce compounds your body needs for energy metabolism.

Here’s what I think happened, in order of how confident I am about each mechanism:

1. The fuel line was clogged - low nutrient absorption

Your small intestine is lined with tiny finger-like projections called villi. This is where nutrient absorption actually happens. The “doormen” that pull glucose from your gut into your bloodstream live here. Antibiotics can strip away the protective mucus layer and cause inflammation in this lining. The villi get flattened. The doormen go on strike.

This explains why I felt temporary improvement after eating, then rapid deterioration. The fuel was going into my stomach, but it wasn’t making it into my bloodstream. I was eating, but the glucose, minerals and other nutrients weren’t reaching the engine.

2. Shutting eyes due to low glucose availability

Your brain is a glucose hog. Unlike your muscles, which can switch to burning fat, your brain relies heavily on glucose, especially during high intensity activity. When blood sugar drops critically low, the brain triggers an emergency response. It starts shutting down non-essential functions to preserve glucose for vital processes. Focus goes. Visual processing gets fuzzy. And it triggers pain (the headache) to force you to stop moving.

The “massive headache” and the overwhelming urge to close my eyes were my brain pulling the emergency brake.

3. Fat metabolism suffered?

This is the piece I keep coming back to but this is something I am least sure of. Good gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. Not only can these act like fuel but they also support fat metabolism in the mitochondria. While this might not have been the major reason, I am pretty sure that the antibiotics directly or indirectly clamped the breaks on the fat metabolism.

Calling off the charity ride

Two rides. Completely different outcomes. One where I felt like I could ride forever, one where my brain wanted to shut down.

The actual London to Brighton charity ride was 2 days after I bonked. It was time to decide: go or not go.

Annie Duke’s book Quit is full of stories about the wisdom of abandoning things at the right moment. There’s a climber who turned back before the summit, not because he couldn’t continue, but because pushing through would have wrecked his chances of ever coming back. He quit so he could try again the following year. And it paid off.

So I called it off.

This felt terrible at the time. Like I had failed. I had trained properly and methodically for an event that promised exhilaration on a sunny day. But it was the wise decision.

If I had quit earlier on that second ride, I wouldn’t have had back issues for the rest of the year. The headache and shutting eyes weren’t obstacles to power through. They were my brain pulling the emergency brake. I should have listened sooner. The back problems that started on that ride crept into my other training and made sure I didn’t meet a single fitness goal for months (ultra first world problems, I know!)

I used to get bothered by the “unproductive” training status alerts on my Garmin. A few months after the back pain from my second ride, I turned them off. It felt good to shut it up. The first ride taught me the science of energy systems in the body while the second ride taught me the art of resting, lowering intensity and shutting up Garmin alerts.